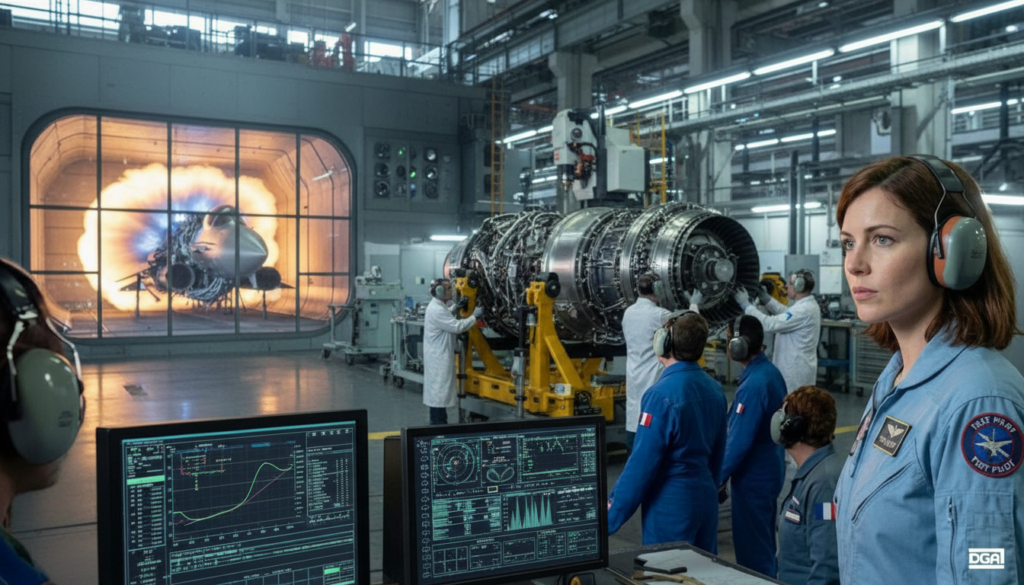

On a dreary, overcast morning at the DGA engine test facility in Saclay, just outside Paris, the ground begins to rumble before anything is visible. Technicians in faded blue overalls move between computers and heavy cables, coffee cups in hand, with a calm, deliberate rhythm typical in the presence of dangerous machinery. Behind a thick glass barrier, a Rafale engine roars to life, fixed to a steel test bench. The sound doesn’t just fill the space—it pushes against your chest. One tiny flaw, one misaligned blade, and the entire system could explode in mere moments. Yet, no one shows fear. What you see instead is absolute concentration.

France’s Strategic Air Power Advantage

A young engineer steps closer to the glass, eyes locked on the exhaust flame. “Listen,” she says. “You’re hearing the only fighter engine in Europe that we can build entirely on our own.” She refers to France. Most people overlook this fact.

From a distance, Europe seems formidable: Airbus dominating civil aviation, multinational fighter programs, shared budgets, and layered cooperation. But when you focus on the heart of a combat aircraft—the engine—the reality changes. France stands almost alone.

The Rafale’s M88 engine, developed by Safran under the constant supervision of DGA, is the only modern European fighter engine whose entire design, testing, and industrial control remain strictly within national borders. No U.S. licenses. No mandatory British, German, or Italian partners. From the digital model to the final turbine blade, every decision can be made in France.

Strategic Leverage Through Technological Sovereignty

This isn’t about pride. It’s about strategic leverage. Step into a DGA test hall, and you won’t find a shiny showroom. Instead, you’ll encounter thick concrete walls stained by exhaust, aging analog gauges beside ultra-high-resolution screens, and cardboard coffee cups resting on racks of sensors worth millions. In the center sits a silver cylinder that seems modest compared to the thunder it produces: an M88, the beating heart of the Rafale.

During test campaigns, engineers intentionally push the engine far beyond anything a pilot would experience. Sudden throttle changes, simulated bird strikes, sand ingestion, violent temperature shifts—cameras track a single blade, just centimeters long, spinning at tens of thousands of revolutions per minute.

The Precision Behind a Fighter Engine

To understand the rarity of this capability, you must zoom in to the millimeter scale. Building a fighter engine isn’t just about raw power; it’s about tolerances so precise that a human hair seems thick in comparison. The DGA and Safran operate like watchmakers wielding a flamethrower.

In one workshop, a technician meticulously fine-tunes the cooling holes of a turbine blade. Each hole is barely visible, laser-drilled into metal engineered at the atomic level to endure extreme heat. The DGA’s job is to define precisely how hot “extreme” can be—and to measure it without compromise.

Here, precision is not just a goal—it’s why a pilot can engage full afterburner and trust that the engine will respond flawlessly.

France’s Independent Engine Design: A Rarity in Europe

Europe is home to many talented engineers, but very few countries retain full sovereignty across the entire process. The Eurofighter Typhoon’s EJ200 engine, for example, is a multinational effort. Each country controls specific modules, software elements, or expertise. While powerful, it’s not fully governed by any single nation.

France, however, chose a different path. From the Mirage series to the Rafale, the country has consistently invested in a national engine lineage, even when budgets were tight and critics argued that cooperation would cost less. The DGA has pushed for domestic advances in materials, aerodynamics, digital simulation, and testing infrastructure, maintaining facilities that many considered unnecessary for a mid-sized power.

France’s Persistence in Maintaining Control

Most governments compromise control to reduce costs. France did not. This persistence is why the country now holds a unique position in Europe. Recent geopolitical shocks have suddenly underscored the importance of this long-term decision.

As tensions rise, export controls tighten, and supply chains become political tools, dependence on foreign approvals turns into vulnerability. Some European aircraft cannot be sold or upgraded without external permission because a critical component or line of code originates abroad. With the Rafale and its M88 engine, France can negotiate directly with partners like India, Egypt, and Greece, and the DGA can authorize adaptations, new variants, and long-term support without external consent.

How the DGA Retains Its Technological Edge

Maintaining this level of expertise requires constant motion. The DGA operates a continuous feedback loop, linking laboratories, test centers, and operational units. Rafale squadrons deployed in harsh desert environments provide engine wear data, which feeds into DGA analysis teams. These teams refine test protocols—sometimes down to a single software adjustment or a new protective coating. The cycle never ends.

The DGA serves as both referee and archivist, recording every failure, micro-crack, and anomaly. Safran might propose a new alloy or a 3D-printed component to enhance performance. The DGA will recreate the harshest conditions just to determine where and how it breaks. The objective is clear: no surprises at 40,000 feet.

The Importance of Continuous Testing and Research

This process can appear rigid from the outside, but engineers within the system see it differently. Many recall late-night tests where data spikes, and the team waits in silence as the systems strain. In those moments, shortcuts vanish. Reality takes over.

States often make the same mistakes: overreliance on foreign partners, neglect of unglamorous test infrastructure, and letting rare expertise fade. The DGA actively avoids these pitfalls. It funds obscure doctoral research on high-temperature fatigue and advanced alloys, and preserves databases of test results older than many of its interns. From the outside, it seems slow. Up close, it’s the only way to sustain such a complex craft.

Conclusion: France’s Sovereign Approach to Engine Production

People may view the Rafale engine as just a product, but in reality, it’s a living ecosystem of expertise. Stop maintaining it for five years, and you cease to be a nation capable of building one. You become a nation that can only purchase one.

The DGA defines future engine requirements based on the Air and Space Force’s needs. Safran converts these into designs and production plans. Operational units provide real-world feedback to refine standards. Test centers push engines to the brink so pilots never have to. Research labs prepare the next breakthroughs in efficiency, heat resistance, and stealth.

The Unseen Monopoly in European Aviation

Understanding the mechanics behind a fighter engine’s roar shifts Europe’s industrial map. France is the only European country with the complete, proven capability to design, build, and certify a modern fighter engine independently. Other nations contribute and innovate, but none possess the same level of sovereign control.

This raises tough questions. Should Europe centralize everything into a few massive programs, accepting new dependencies? Should each country preserve fragments of autonomy at higher cost? Or does the French model—a long-term national investment anchored by a strong state actor like the DGA—offer a valuable template? There are no easy answers, but it’s clear that this technical detail will significantly influence future combat systems, export freedom, and political decision-making.

When a Rafale flies over Paris during the 14 July parade, there’s a quiet message embedded in its engine’s roar. It speaks of a country that chose, decades ago, to understand every turning blade—and to never let that knowledge slip away.